German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has been much criticised by NATO allies, as well as by the Western press, for his hesitant stance in the Ukraine conflict. While the German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock in a statement in Strasbourg frankly speaks of a war of the West against Russia, the German Chancellor has so far refrained from using strong words. He probably has reasons for this. What could they be?

Many Germans are rather unhappy with the course of the war in Ukraine and would like nothing more than a peace agreement. A manifesto drafted by Sahra Wagenknecht and Alice Schwarzer sums up these feelings. Is there an explanation for the chancellor's behaviour here? Probably not yet.

The view from outside

On 23 February 2023, the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, known for its critical attitude towards the US government's geo-political stance, wrote:

"Russia's invasion of Ukraine has led to a radical shift in German foreign and security policy. This includes measures that would have been unthinkable a year ago, such as the delivery of heavy weapons to Ukraine."

However, this change has also led to significant divisions in the German governing coalition and unease in parts of German society. There is also concern among Germans, especially in industry, about the dangers to the German economy if Germany has to follow the US in isolating and weakening the economy of China, which is an important market for German exports.

These issues are crucial not only for Germany but also for the European Union and the future coherence of the transatlantic alliance."

The view from within

In his new book "Führung und Verantwortung" (Leadership and Responsibility), published at about the same time by Siedler Verlag, the chairman of the Munich Security Conference, Christoph Heusgen, outlines the leadership role of Germany in the world, which Sigmar Gabriel, for example, would find implausible (see below), but which ex-Federal President Joachim Gauck already called for in Munich in 2014.

The Düsseldorf economist and diplomat, former chief of staff to EU foreign affairs envoy Javier Solana and foreign policy advisor to German Chancellor Angela Merkel for 12 years, believes that the time of "leading from behind" is over: "The German government must realise that leadership and responsibility cannot mean always being the last to do the right thing."

Ex-vice chancellor and former foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel recently ventured the prediction in a conversation with journalists: "I'm relatively sure that Ukraine will get fighter jets."

Then he added the crucial sentence:

"But the political decision whether we participate in this is not a German one: my advice would be to leave the lead where it is, with the US."

In his government statement, Chancellor Scholz provided only vague slogans such as "The path to peace requires courageous action", but hardly any useful information.

For the flash visit to the White House, journalists were not allowed on the government plane for the first time in his term of office. The usual White House press conference was cancelled. For diehard democrats, this should be a warning signal.

It does not look like a new leadership role in Europe or even in the world, more like vassal loyalty to a mighty hegemon. It takes blinkers to see this state of affairs as the best of the options.

Looking beyond the horizon

Perhaps however there are currently no good options around for a dwarf state like Germany - at least not in the short term.

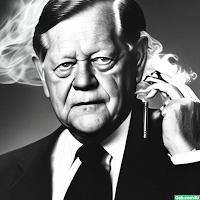

If we are looking for a German politician with a sober assessment of the situation and a clear view of the options, we probably have to go back a few years.

At his last public appearance at an SPD party conference (2011-12-04), the then 92-year-old seemed fresher than many a delegate in the hall. He vehemently opposed "the harmful German-national strongmanism". When nine billion people swarm the earth in 2050, the old continent will no longer produce 30 per cent of the world's economic output, as it did in 2011, but only a tenth of that. By then at the latest, a country alone will "no longer be measured in percentages, but only in parts per thousand".

A lucid vision indeed. When former Bundestag President Wolfgang Thierse asked him when the Federal Republic would finally become a normal country in Europe, Schmidt's answer was as short as it was sobering: "Not in the foreseeable future.” After two wars in a century, generations of Germans would still have to live with their historical burden and the latent suspicion of neighbouring European countries, he predicted.

Taking these thoughts further, Germany's role is more likely to lie in close integration with neighbouring European countries that have experienced a similar social moulding and which carry the same values in their firmware. A Rütli oath at the European level would at least enable us to be measured again with a percentage share in world affairs instead of per thousand.

No comments:

Post a Comment