"Anyone who has ever gazed into the glassy eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think twice before starting a war."

These words are attributed to Otto von Bismarck. Given his political toughness, determination, and ability to enforce during his tenure as Prime Minister of Prussia and later as the first Chancellor of the German Empire, earning him the moniker "The Iron Chancellor," he was not known for sentimentality. Power politics was not an alien concept to him.

The current head of the Foreign Office, established by Bismarck, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, who renamed the so-called Bismarck Room and removed a painting depicting the Chancellor, seems decidedly more bellicose. That our top diplomat saw Germany already at war with Russia could be dismissed as a slip of the tongue.

Yet, signals are mounting that we may already be on the brink of a pre-war era. At a closed security conference in November 2023, a former senior European official even questioned whether World War III might have already begun, noting that not all belligerents had entered World War II at the same time. The unspoken reference to the multinational conflict at our doorstep, which seems to have no end in sight yet harbours enormous escalation potential, was understood by all present.

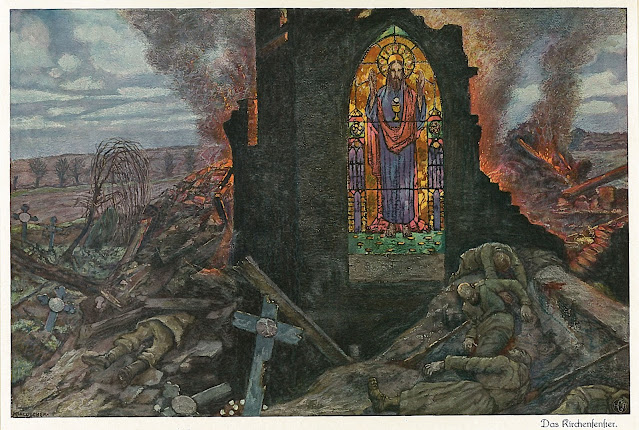

The Enthusiasm for War

The political class's fervour for war across nearly all German parties and much of Europe is unmistakable.

On February 28, 2024, the newsletter Europe.Table reported a new strategy by the EU Commission, marking a "paradigm shift towards a war economy."

Shortly before, French President Emmanuel Macron stated that the deployment of Western ground troops to Ukraine could not be "excluded."

Outspoken hawks like Anton Hofreiter of the formerly pacifistic party "BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN," who supported the delivery of offensive weapons to Ukraine, are evident.

FDP defence politician Strack-Zimmermann expressed "astonishment" when the German Chancellor clearly rejected the delivery of Taurus cruise missiles to Ukraine, eliciting criticism from other parties.

Not just in Europe: In early 2023, Victoria Nuland, the third-highest U.S. diplomat, encouraged Ukrainian forces to continue attacking Russian military bases in Crimea, at the expense of Ukrainian and Russian populations. Even former U.S. President Donald Trump called her a warmonger, contributing to our closeness to a Third World War like never before.

It's noticeable that those advocating for further escalation of this proxy war have not experienced war themselves. They likely cannot imagine the horrors it entails, horrors that deeply scar all involved, burdening individuals for life and passing through generations.

Or, as Harald Kujat, a retired general of the German Air Force, former Inspector General of the Bundeswehr, and Chairman of the NATO Military Committee, describes the debates on weapons in Germany:

"There are people on German television with ten minutes of speaking time accusing the Chancellor of lying, who cannot tell a rifle from a cucumber."

The Lure of Wars

In 1911, Norman Angell, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 1933, published a ground-breaking book titled "The Great Illusion," arguing that war had become economically senseless. He believed that the interconnectedness of nations through trade and finance would prevent major conflicts.

His central thesis was that nations would not derive economic benefit from war, as it would disrupt global trade and prosperity.

Angell never declared war impossible, but his ideas resonated and influenced later discussions about war, peace, and conflict. His assumptions were based on a "chivalrous" treatment of defeated peoples, rooted in the Peace of Westphalia established in 1648, which lasted about 150 years. Apparently forgotten were the earlier, more archaic forms of war, where only one could survive, and genocide was a logical outcome.

Later, even Angell himself had doubts, and when 12 foreign ministers from Canada, the United States, and ten Western European countries signed the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington on April 4, 1949, founding NATO, Angell, by then knighted, supported the collective defence pact despite his pacifist background.

Wars seem to pay off, and as John Mearsheimer articulates in his widely cited book "The Tragedy of Great Power Politics," they are occasionally inevitable.

But is the damage not greater than the benefit?

And then there's the greatest of all technological threats. Martin Hellman, cryptography pioneer, co-inventor of the Diffie-Hellman algorithm, Turing Prize winner, and advocate for world peace, says: If we continue to wage wars, it's only a matter of time until nuclear bombs explode.

The "Mutually Assured Destruction" (MAD) doctrine, where superpowers possess enough nuclear arsenal to completely annihilate each other, was supposed to offer sufficient deterrence and lead to stability. The nuclear deterrence theory maintained

a kind of balance of terror during the Cold War between the USA and the Soviet Union. Without the MAD threat, however, these weapons of mass destruction were recklessly used, as proven by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, resulting in an immediate loss of about 200,000 lives.

MAD may have prevented nuclear wars, but wars continued to be waged below the nuclear threshold. The United States, protected by two large oceans and bordered by far weaker states to the north and south, last experienced war on its territory on December 7, 1941, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Before that, it was during the War of 1812 between the USA and Great Britain and its colonies.

The temptation to wage wars is apparently great when one's own territory is unaffected. It's a cynical argument, but does the benefit outweigh the potential harm? At least for the arms industry, as evidenced by the United States, it seems to. U.S. arms manufacturers have the largest market share in the world. Forty companies from the United States are listed in the SIPRI list of the world's largest arms manufacturers, generating almost $300 billion in 2021, roughly half of the global revenue in the arms trade. For some stakeholders, wars thus pay off.

This also applies to wars that result in the annexation of territories promising strategic benefits, whether military or economic. Genocide is not a goal, at least not an avowed goal anymore, but a tolerated collateral damage. Ethnic cleansings as a result of wars continue. Whether it's our NATO partner Turkey in Syria, or its allied regime in Azerbaijan with the conquered Armenians, criticism is only expected from those who fall out of favor for other reasons. Wars still pay off if carefully dimensioned, camouflaged, justified, and conducted at the opportune moment.

But does this still hold true for larger conflicts, where an attacker can expect worldwide impairments or even damage on their own territory? We now rely on a vulnerable global infrastructure whose failure would end civilian life as we know it.

In February 2024, there was heated discussion about an anti-satellite space weapon that Russia allegedly developed, which could potentially destroy the low Earth orbit for everyone.

"If someone dares to detonate a nuclear weapon in the high atmosphere or even in space, it would be more or less the end of the usability of these global commons," said Major General Michael Traut, responsible for Germany's military space command, according to Politico Europe. "No one would survive such an action - no satellite, whether Chinese, Russian, American, or European." In such a case, satellites currently orbiting the Earth would turn into debris, creating dense fields of wreckage.

However, the civilian everyday life of the population on Earth, with telephones, computers, navigation, television, energy supply, and dependent services, in turn, depends on functioning satellites. Satellites thus constitute global, critical infrastructure. They are currently unprotected, perhaps even undefendable.

But what about critical infrastructure on Earth, i.e., the facilities, systems, services, and networks crucial for a society's functioning? They typically include:

- Energy supply: Power plants, electricity grids, oil and gas pipelines.

- Transportation: Airports, ports, railways, roads, and bridges.

- Communication: Telecommunication networks, internet infrastructure, satellite communication.

- Water and wastewater: Water treatment plants, sewage networks.

- Healthcare: Hospitals, emergency services, medical facilities.

- Finance: Banks, stock exchanges, payment processing infrastructure.

- Government facilities: Government offices, defence installations, data centres.

- Food and agriculture: Food production, warehouses, food distribution.

Apparently almost the entire infrastructure is to be considered as critical infrastructure. Its failure or impairment can have serious consequences.

Governments, businesses, and international organizations officially see the security and protection of critical infrastructure as a priority to ensure a society's well-being. This is already inadequately achieved in peacetime. We are far from comprehensive resilience, i.e., resistance to threats.

That the critical infrastructure of advanced industrial nations can still be effectively protected in a war scenario on their own territory is simply unimaginable. Our globally interconnected economy is easily vulnerable, our global supply chains sensitive and prone to disruption, our worldwide communication strands easy to interrupt.

Threats to the global supply chains we depend on are already diverse. They range from natural disasters to political instability to technical failures and pandemics. Some of the main threats are:

- Natural disasters like earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, and wildfires can block transport routes, damage infrastructure, and disrupt trade. Hurricanes like Katrina and Sandy, earthquakes like the Tōhoku earthquake in Japan, and wildfires in Australia and California have blocked transport routes, damaged infrastructure, and destroyed production facilities.

- Pandemics, health crises, disease outbreaks can lead to supply chain disruptions, as we recently experienced with the COVID-19 pandemic. It led to production shutdowns, factory closures, transport interruptions, labour shortages, and a huge increase in demand for certain products like medical equipment and household goods.

- Cyberattacks, whether criminal or politically motivated hacker attacks on information systems and logistics networks, can disrupt the operation of supply chains, cause data breaches, and compromise security.

- Political instability, local conflicts, terrorism, political unrest, and trade disputes can lead to border closures, sanctions, trade embargoes, and other restrictions.

So, the trade disputes between the USA and China and other countries led to tariff increases, trade embargoes, and uncertainties that affected international trade.

A recent attack on the German railway system severely disrupted the already fragile train traffic between Berlin and Hamburg.

On February 24, 2024, at least three undersea cables off the coast of Yemen were severed, disrupting worldwide internet and telephone connections. The cable Asia-Africa-Europe 1 (AAE1), also used by the German internet node operator DE-CIX, was cut. It is suspected that a cargo ship sunk by local Houthi rebels during wartime conflict severed the cable.

Conflicts are listed here only incidentally last. In reality, they can have the most significant impact. Even below the threshold of a large war, we thus have to accept massive economic losses and decreases in prosperity and quality of life, but also in human lives. The impairments in conflicts where one warring party can use clear military superiority remain limited, affecting the defeated or those uninvolved in the conflict or even taken as a price for victory.

The threshold to a large war can easily be crossed, whether intentionally or from an unforeseen "compulsion." Such a conflict with global implications has been looming for a quarter of a century; since China and the USA lost their common enemy with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the USA felt threatened by China in its role as a global hegemon.

This increasingly escalating conflict between the two countries already shows many signs of a Cold War. The parallels to the situation before World War I, when the then unchallenged world power England felt threatened by the rising, united Germany, are unmistakable. Just as easily as back then and without further conscious decisions, the "cold" war can become a "hot" war - the 3rd World War.

Even if this war, out of fear of mutual total annihilation, were fought exclusively with so-called "conventional" weapons, we must expect the collapse of entire economic spaces and civil society in larger geographical areas, associated with a very significant decrease in population. No one has yet explained how and for whom such a conflict could still "pay off."

The basic assumption that it would remain at "conventional" engagements could just as easily prove erroneous. Before a nuclear power admits defeat, it might indeed resort to the extreme, following the motto: "If we must go down, then please with a big bang. And then we'll take as many with us into our grave as we can."

In this context, Albert Einstein is often quoted as saying, "I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones."

Can we really still afford waging wars?